The Museum as Giftshop

In 2008 Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk published his novel The Museum of Innocence. Set in Istanbul from 1975 to today, the story is woven from memories catalysed by objects that Kemal, the protagonist, has taken or stolen from Fusun, his love. These talismans of their short-lived affair keep his passion alive, and on the death of her parents he buys the house she grew up in, transforming it into a museum of their love, creating a home for his collection.

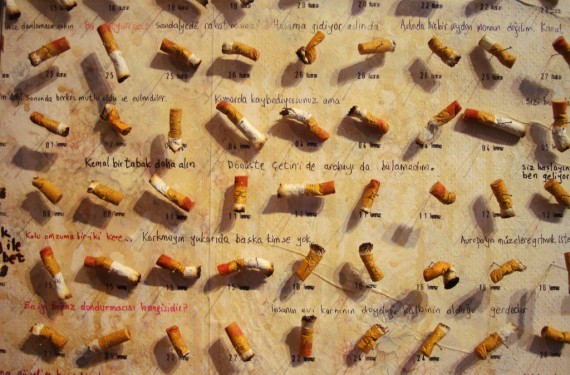

In 2012, Pamuk opened an actual Museum of Innocence in Beyoglu, Istanbul – in a building precisely as described in the novel – filled with the objects that feature in the text, from a quince grater (notable subject of a particular chapter) to handbags, ashtrays and a child’s tricycle. The novel even contains a printed ticket that grants entry to its museum-proper. It is an uncanny experience to visit. As you enter, the first wall you encounter is dedicated to the butts of the 4213 cigarettes smoked by Fusun. Pinned to a wall like ten thousand twisted butterflies, an overwhelming display of lipsticked filters.

The museum disrupts the implicit assumption we make as visitors to institutions such as these, which lies in the inviolability of the museum’s relationship to ‘reality’, to a history that happened, somewhere, once – to ‘truth’, of some kind. The Museum of Innocence, on the contrary, is a museum that makes manifest fiction and imagination. The structure of time is rendered ambiguous: Pamuk creates a past for a present that never existed. A feeling of disquiet arises from its nonchalent co-option of the associations of authenticity exuded by the model Museum; it uses its tropes and iconographies to turn fiction into fact (or, more accurately, the kind of fact inevitably distorted by exhibition, to which most museum material is subject). The legitimacy of the museum environment confers on the novel a ‘reality’ of existence it didn’t have before, and in turn has its own status as truth-space reinforced by the existence of its textual counterpart.

However, the Museum of Innocence is most productively read as critique in this sense; revealing the pernicious role of art instititutions in establishing powerful discourse and inherently partial narrative. Walter Benjamin’s concern with Alfred H. Barr as the ‘writer’ of the West’s predominant History of Art through MOMA finds parallel in Pamuk here – a literal author – who writes himself into his novel as the transcriber of Kemal’s tale, and then fulfils that prophecy in real space and time. Ultimately, Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence reminds us that all museums constitute inventions, and perpetuate versions of history that are themselves a kind of fiction. Yet, Pamuk’s implicit criticality of history-telling and object fetishism constitutes the reverse of his Museum’s primary intention, and cannot resist the sensation of discomfort a visit engenders.

Pamuk’s loose thread comes, it seems, in the form of the giftshop, a site of particular ambivalence, of bad taste in the mouth. Tucked at the very end of one’s journey through the Museum, the shop is stocked exclusively with Pamuk products. His books, postcards, posters, keyrings, etc, pepper the shelves, (photographs in the museum itself are expressly forbidden). The shop feels like a chink in Pamuk’s armour, where the latent narcissism of his novel-museum finally bleeds into the visitor’s consciousness. One can’t help hear his bank balance pinging.

The shop’s commercialism is destructive because it collapses the sense of communion the museum’s experience creates – between the world of the novel and the space of its actuality – which is unique to those who have read the book and lived in its pages. The giftshop suddenly exposes the museum as in a mirror – a vanity project, a fiction, packaged as clever conceit – ultimately about the man behind it. Pamuk’s giftshop is a site of rupture, where the museum’s ‘innocence’ – if such a thing really is expressed within – is negated by the commercial concerns of its store.

The question is begged, however, of how different Pamuk’s museum really is to any other? The giftshop is a productive vehicle for thinking through the operation of all museums along such lines of vanity and fiction. How have the museum and the giftshop mapped onto each other historically? Can this process reveal something about museology today?

The Louvre, for instance, though its palace and holdings have a long history, had its collections extended significantly by Napoleon 1 in the late eighteenth century. It was his rule that contributed most to the development of the modern Louvre museum. Napoleon co-opted the space primarily to house ‘conquests of war’, the countless works of priceless Renaissance art his armies stole as they decimated Italy on their campaigns. Back in the capital, with these on display, the Louvre became the public site of Napoleon’s broader imperial aspirations – to make France the modern inheritor of the Roman empire, and Paris into a new Rome.

Is there not a parallel to Pamuk’s Museum here, a one-man show of vanity and pride? The Louvre was renamed La Musée Napoleon in 1803; the Museum of Innocence feels ultimately like a temple to Orhan Pamuk. Napoleon’s theft echoes nicely here with Pamuk’s very narrative – in the novel Kemal steals his conquests (of love, this time) from the untouchable Fusun.

The Museum as we know it today performs the role of arbiter of history, taste, quality, authenticity, truth. And yet underpinning it is surely also the history of the giftshop – concerned with vanity, appearance, uniqueness, exclusivity, power, rarity and caché. These concepts dominate contemporary rhetoric around museum giftshops also:

‘Smithsonian museum stores carry a collection of gifts curated just for you. Each museum features unique merchandise, so be sure to shop them all.’ Smithsonian, Washington

‘Be bold! Scarves and accessories in colours of Matisse.’ Tate Modern, London

‘The MOCA Store develops and distributes products created with artists and designers, exposing a broad audience to new and exciting work from the contemporary art world.‘ MOCA, Los Angeles

The rhetoric of ‘curated’ gifts and art world development indicates how the very language of the giftshop maps on to the process of the museum – their continuity is clear, their premise indistinguishable. The very word ‘gift’ feels implicitly connected to the ‘gift of knowledge’ transmitted within the sanctity of the museum space. The online space of the giftshop also frequently reminds you that your purchase is there to fund the work of the museum: ‘your purchase helps the Smithsonian bring exciting learning experiences to everyone!’; ‘Your purchase supports the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its programs’. Explicit connection is made between the role of the visitor (who receives enlightenment) and its pay-off: the expectation that the visitor has a responsibility to continue their experience for others (to pass on the gift) through their credit card in the giftshop. Museum entry is not limited to a ticket – but further funded by your transactions in the commodified zone.

Just as the museum’s narratives constitute fractional versions of historical representation, the giftshop’s effect on product is ultimately reductive: revolving around reproduction, a process that requires minutuarisation, shrinking paintings into postcards, sculptures into key rings, and flattening images to wrap around mugs and plaster onto iPhone covers. This is the dual work of the giftshop: to continue and extend the premise of its museum-parent, within a safely commercial remit (the museum’s own legitimacy relying on distance from overt financial concerns), and to simultaneously reduce and distort its content for capital. Pamuk’s project combines these with the effect of making museum and giftshop ultimately indistinguishable, one and the same.

The process of mapping giftshop onto museum is complete, once more in the Louvre, which is building its largest and most public giftshop on Saadiyat Island, in the United Arab Emirates. The Louvre, Abu Dhabi, set to open next year, paid $525 million to its sister museum to be associated with its name. It represents the masterful feit of packaging nebulous centuries of history and selling them in the guise of culture to states without clear historical trajectories, seeking footholds of legitimacy in the contemporary global landscape.

The giftshop exposes pre-existing models of museological operation – whereby the museum, both autonomous and legitimate, generates revenue for corporations, whose pockets open underneath. The now-prerequisite sponsorship of major exhibitions by corporations (most frequently banks), and projects like the Unilever Series at Tate Modern, are successes lauded on Museum websites:

'Harry Winston's sponsorship of the ground-breaking major V&A exhibition Hollywood Costume delivered impressive return on investment for the jeweller, proving particularly successful in raising Harry Winston's brand profile, generating PR and building customer relationships'. V&A, London

‘“The Guggenheim is one of our most creative and dynamic sponsorship activities. Our partnership with the Guggenheim has produced tangible benefits throughout the company and around the world.” —H. Kettenbach, Head of Corporate Communications and Arts Sponsorship, Hugo Boss’. Guggenheim, New York

As the above suggest, museums themselves constitute the most exclusive giftshop stock, available to corporations desirous of raised revenue, a cultural profile and other such ‘tangible benefits’ bestowed by relevant exhibitions. One can imagine H. Kettenbach shopping for the ‘right’ exhibition for Hugo Boss to support , just as Harry Winston sourced the V&A’s Hollywood Costume exhibition for its diamond business. One can imagine the sponsor itself commissioning a tailor-made exhibition from the museum itself (Joseph Beuys for Deutsche Bank?), a process that would uncannily mirror Pamuk’s novel-turned-museum.

Indeed, Pamuk comes full circle in this too. Since the opening of his actual Museum of Innocence, Pamuk has published The Innocence of Objects, a catalogue of the museum’s contents. The fictional-novel-turned-actual-museum has generated its own objective catalogue, inscribing upon itself a further layer of pseudo-authenticity. Such a catalogue yields the veiled fiction of the museum back to the realm of literature once more – to the characteristics inherent to catalogue: quietness, focus, anthropology, the archive. The reverse, ultimately, of the Louvre’s upsizing in Abu Dhabi, where one can foresee each artwork blown up XXL as in a mail-order brochure, presented to the public as swollen, ballooned versions of their historical selves.

Has the giftshop’s prerogative – to extend the museum and reduce its forms, to reap its benefits and inform its content – become the raison d’etre of the museum itself? Or perhaps, as Pamuk’s museum suggests, the museum was a giftshop all along.